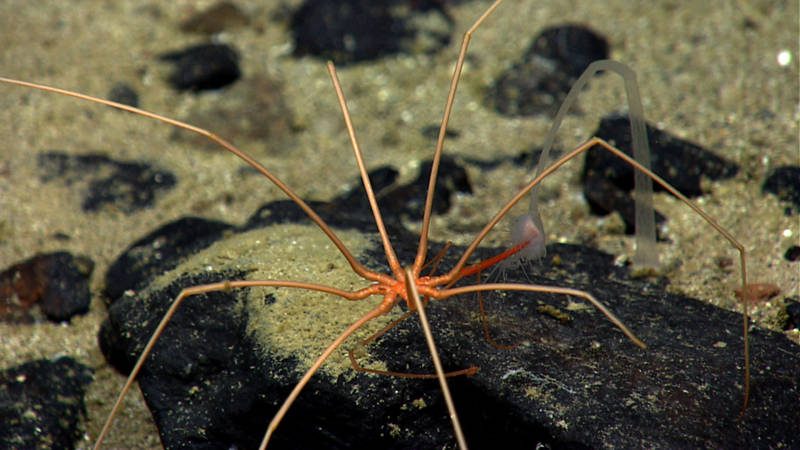

The team is trying to tease out what else in the environment could contribute to these critters’ gigantism. However, there could also be other factors. “In terms of supply and demand that means that there’s a lot of supply and not very much demand,” Woods said. But in cold polar climates, those reactions slow down and so do the creatures that live there, meaning they use oxygen at lower rates. Oxygen fuels the chemical reactions that drive a creature’s metabolism by converting food into energy. "It could be that these animals have no predators here” “In the water it’s just all oxygen almost everywhere,” Moran said. Atmospheric gases like oxygen dissolve more easily in cold water than in warm water, so the frigid oceans around Antarctica are saturated with the stuff. The prevailing theory is that a combination of plentiful oxygen and cold temperatures lets these organisms grow to sizes that are impossible elsewhere. Why these underwater critters grow so big is an open question, one that Moran and her team are diving under the sea ice to investigate. They’re known to scientists as pycnogonids, and only picked up the spider moniker because most species have eight legs. Instead their nearest relatives are horseshoe crabs. “They’re very poorly known for a group that’s that important here and has that many species worldwide,” Woods said.ĭespite their name, sea spiders are only distantly related to the web-spinners on land. The researchers pass by large sponges, brightly colored sea anemones, fields of sea stars and even the occasional playful seal while looking for their eight-legged quarry.īack on shore, they’ve prepared a slew of experiments to test these sea spiders’ metabolism, the strength of their legs, how well they can cling to the ocean floor and even their grooming habits. When you go down you can see for hundreds of feet around.”īelow the featureless, barren ice surface, the sea floor is alive.

“It’s really cold,” Steven Lane, a doctoral candidate at the University of Montana, said about diving under the ice. After donning extra-insulated layers for their diving suits, strapping on scuba tanks and gathering up their collection nets, they plunge into the icy water below.īret Tobalske (top) and Art Woods (bottom) suit up to collect more sea spider specimens from below the Antarctic Ice. Several times a week the team makes their way to one of bright orange diving huts set up on the sea ice. Throughout the austral summer season, the team is collecting dozens of specimens of different sizes and species by diving under the ice covering McMurdo Sound. She and her team are focusing in on sea spiders, spindly marine creatures that look like a cross between a crab and a daddy-longlegs. “It’s like things can be big if they want to.” “There are normal-sized ones too, it’s not like something is making everything be big,” Moran said. Sponges, sea stars, worms and other invertebrates can grow to tremendous sizes in the waters off the coast of Antarctica. “That’s true across many species of marine organisms.”

“In general things that live in warmer water and tropical waters tend to be much smaller than the species that live down here,” Woods said. The National Science Foundation (NSF) manages the Program, which coordinates all U.S.

Antarctic Program-supported team led by Amy Moran at the University of Hawai´i at Mānoa. It’s a phenomenon called “polar gigantism,” and Woods is studying these marine giants as part of a U.S. “We spent a lot of time off the coast of Washington in June of this year looking for sea spiders, and the biggest one we found was about the size of a dime,” said Art Woods, an associate professor of biology at the University of Montana.īut, he continued, it’s not uncommon to find ones as big as dinner plates in the Antarctic. Amy Moran peers through a microscope at recently hatched sea spiders as Caitlin Shishido looks on.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)